Since 1996 we have been told that, “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation.” Known as “the generations campaign,” this masterstroke of luxury marketing became a literal textbook example. The message was clear: A Patek Philippe is a timeless heirloom, the very antithesis of a trendy watch.

Half way through 2024, Patek Philippe switched to a campaign that more strongly asserts the brand’s refusal to feed trends. The new slogan reads “There Is No Star,” and the copy stretches out in justification: “Why does Patek Philippe have so many collections? Because…each one allows us to innovate and to express ourselves. [N]ot all people who like our watches, like the same watch. It is for this reason that there is no hero watch at Patek Philippe. There is no star.”

The print ad in a the latest issue of Robb Report.

I can only read Patek Philippe’s new campaign as an indictment of what many watch aficionados refer to as Audemars Piguet’s “Royal Oak problem.”

The Royal Oak is an avant-garde Gerald Genta-designed watch with an integrated bracelet from 1972. Today, the Royal Oak is not just Audemars Piguet’s hero watch but has arguably overtaken the watchmaker’s brand identity. Patek Philippe is obviously going to great lengths to prevent its own nautically themed, Genta-designed, integrated bracelet watch from 1976, The Nautilus, from overtaking the Patek brand. When Patek dropped the Cubitus in October of 2024, the statement was clear: the Nautilus will not be the star of the show, but will share center stage with multiple elegant sports watches with integrated bracelets, including the Aquanaut. If the Cubitus tells us anything, it is that Patek Philippe is not looking to focus on the Nautilus.

Royal Oak Selfwinding and Royal Oak Selfwinding Chronograph in 18-Karat White Gold and Diamonds

Audemars Piguet

The problem with trendiness for luxury brands is not only that it dictates a passing fad, but also that the air of exclusivity is tarnished. This latter point is true even when the product is unavailable at retail, as little exclusivity adheres to a product over which everyone and their cousin are going ga-ga. Exclusivity extends to knowledge, not just ownership. All told, trendiness is low-brow, and low-brow just won’t do for luxury brands. It is from this perspective that so many people (present company included, obviously) wonder whether Audemars Piguet has a Royal Oak problem.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Selfwinding Rainbow Watches

Audemars Piguet

Try to bring another Audemars Piguet model to mind. I find it difficult. There’s the initially ill-received Code 11.59, a watch series launched in 2019 that some ascending collectors feel they’re pressured to buy before gaining access to the coveted Royal Oak. No matter how complicated and wonderful the movements packed into the Code 11.59, the often hostile attitude toward the new model only highlights AP’s problem: Play the hits, or get off the stage.

Audemars Piguet Code 11.59 Flying Tourbillon Chronograph

Diode SA – Denis Hayoun

Gerald Genta Mania

None of this was a problem for Audemars Piguet until (I estimate) around 2018, when mania for Gerald Genta—the renowned designer of the Royal Oak—took hold of the global watch community. Due to algorithm-assisted Instagram influencers and a new breed of rabid watch journalist, horological fads were moving faster than ever before. Pretty much every watch journalist I know (including yours truly) began running stories about Genta as the most important watch designer of the 20th century. Horological neophytes spoke as if they were Gerald Genta aficionados. Genta’s sketch of a Royal Oak sold at auction for $727,000. A British journalist posed for photos at an important watch event while wearing a tee shirt with “Gerald Genta Rules” scrawled across the front.

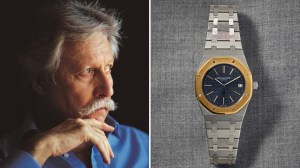

Gerald Genta and his personal Audemars Piguet timepiece.

Sotheby’s

Then Royal Oak fever broke out. Prices shot up. Royal Oaks—new, used, pre-owned and vintage—sold out everywhere. So, naturally, Genta’s second integrated bracelet watch, the Patek Philippe Nautilus, became the one to get. Especially Patek’s stainless steel 5711, the reference that watch bros started calling “pure unobtanium.” (I am happy to report that the term “unobtanium” has grown passé since the watch bubble burst last year.)

Patek Philippe Nautilus Ref. 5711/1A

Courtesy of Patek Philippe

By mid-pandemic, most brands had jumped on the bandwagon with pre-existing, re-introduced, or totally new integrated bracelet watches: Moser, Chopard, Girard-Perregaux, Bell & Ross, Piaget, IWC, Zenith, Oris, Laurent Ferrier…I could go on and on naming brands that sent me press releases with news of their integrated bracelet watches. Even Vacheron Constantin began selling out of its Overseas, a gorgeous and interesting watch notable for not being designed by Gerald Genta, a fact which still renders the Overseas the less hip cousin to the Royal Oak and the Nautilus. Even so, the entire Horological Holy Trinity (Patek, AP and Vacheron) was in danger of getting stuck in the era of disco, cocaine and polyester—which was perhaps unbecoming of brands dating back centuries.

Moser Streamliner Small Seconds Blue Enamel

H. Moser & Cie

Kill Your Heroes

Cutting through all that hype and stealing headlines, Patek killed its hero. After one final version in conjunction with Tiffany & Co.—a limited edition that provoked full-blown tizzies from grown men over a pastel-blue I’d always associated with Audrey Hepburn and my mother—Patek Philippe turned its back on the bros and converted the 5711 into the purest form of unobtanium: Discontinued!

Patek Philippe x Tiffany & Co. Ref. 5711

Patek Philippe

Patek Philippe was obviously going to great lengths to avoid the Royal Oak problem. But I’ve come to understand that Patek Philippe had more in mind when it canceled the 5711, because that’s not all Patek did at the time.

I was hanging out with a Patek Philippe dealer in Copenhagen in 2022, who pointed out that Patek was trying to get people to realize that its real innovation—and, as he put it, “the watch that you’d climb Everest with”—was the Calatrava. A cartoon lightbulb appeared over my head.

Patek Philippe Calatrava “Clous de Paris” Ref. 6119R-001

Patek Philippe

The Calatrava placed seventh in our ranked list of the 50 greatest watches of all time, one place above the Nautilus. The typical story we tell about the understated Patek Philippe Calatrava of 1932 contends that it was the first relatively affordable Patek Philippe, a wise market adaptation to the fall of royalty and the rise of the middle class in democratic Europe. That story is true. But what people overlook is that the Calatrava was the first round wristwatch with lugs cut from a single piece of metal (lugs had previously been welded onto round cases). The Calatrava’s totally innovative case architecture is so common now that it’s nearly impossible to imagine that in 1932 that shape was radically futuristic. The Calatrava remains Patek’s greatest contribution to the form-factor of wristwatches, and the Nautilus will forever remain an imitation of Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak. The Dane was right.

The 36 mm case of Andy Warhol’s Patek Philippe Calatrava shows the integration of the case and lugs.

Sotheby’s

I began to see that Patek was downplaying the Nautilus and its younger sibling the Aquanaut while simultaneously offering the Calatrava in various colors, styles and complications. The Calatrava was going from understated dress watch to—we can’t say hero watch, exactly—but a celebrated Patek innovation with a deep and important history. The only Patek ever produced for military service, for example, was a Calatrava, a model Patek recreated with abundant field-watch vibes in the 5226G of 2022. Similarly, the pilot-watch spirit of various Travel-Time Calatrava references only drives the message home that this deeper history is extremely important to Patek Philippe.

Patek Philippe 5226G Calatrava

Jean-Daniel Meyer

Just last month Patek told my colleague Paige Reddinger that the (gorgeous) solid-gold Ellipse on its intricate chain bracelet is generating a lot of interest, suggesting that the strategy to downplay any single hero watch and proliferate across collections is not just an ad campaign, but a strategy that Patek Philippe is backing up in the proverbial metal. In an interview with Bloomberg last year, Patek Philippe president, Thierry Stern, said a new collection (presumably to rival the Nautilus and Aquanaut hype and aimed at a youthful client) is on the horizon from Patek Philippe this year.

Final Thoughts (Which Probably Deserve Their Own Essay)

I think it’s fair to say that Patek Philippe has avoided the Royal Oak problem, but was it really a problem?

I will admit that I find Patek’s strategy admirable. I like it when brands stay the course, remain true to their deeper history, and refuse sway with trends. But I think I like this steadiness because it offers me the illusion of sanity in a world that often feels anything but. In this regard, I suppose I am a traditionalist. And maybe I’m exhibiting a little Eurocentrism, as well.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept “Black Panther” Flying Tourbillon

Audemars Piguet

This admission brings me to what may be an important point about Audemars Piguet: Of all the brands in Switzerland—and most notably as a member of the Horological Holy Trinity—AP is putting people of color and women far forward in its apparent list of priorities. We see this in its ambassador choices, in the avant-garde designs of the Royal Oak (one of which includes the comic character Black Panther) and—perhaps even more poignantly—in the book the brand sent me over the holidays called Ghetto Gastro: Black Power Kitchen. If nothing else, this is all very American for a Swiss brand. While Patek Philippe speaks of its diversity of collections, perhaps Audemars Piguet—with its one big hero watch—is working toward an entirely different kind of diversity.

And with that, I’ll suggest that we could come at this topic from a whole other angle: Maybe it’s Patek Philippe with the Royal Oak problem to deal with.

Authors

-

Allen Farmelo

Allen Farmelo is Robb Report’s digital watch editor. His writing and photography have appeared in Fortune, Hodinkee, WatchTime, International Watch, and many others. When he’s not obsessing over…

Credit: robbreport.com