When I was twenty-four years old, I bought a five-acre farm in rural Pennsylvania, about an hour east of Pittsburgh. In the eight years since moving in, I’ve been marking time by the numbers: thirty-seven chickens in my flock, one barn cat who had a litter of five kittens, two beat-up trucks that rusted by the barn, and last winter, the fourth warmest on record in 150 years.

I mention these numbers because they are all related to one another. They serve as a sort of arithmetic I play in my head to better understand the land I am, sometimes begrudgingly, the steward of. If it gets any hotter in the summer—a concerning upward trend these last few years—the chickens will stop laying to conserve their energy. Warm winters mean deer populations explode, so planting a vegetable garden is almost useless come springtime. Violent summer rains, which used to be rare, now mean more rust on the pickup I’ve been promising to sell. Everything on this farm is connected.

But this sort of living gets lost in translation when I speak to my colleagues across New York, London, and Zurich. My friends in larger cities seem to think it’s quaint that I’m playing farmer, but I have a real concern in what I’m seeing in this little pocket just off the Appalachian Mountain range that is hard to explain unless you live where you can see it firsthand. It wasn’t until I made it to Helsinki in October that I felt that environmental concerns weren’t an abstraction. Instead, it can play a large part in personal identity and, by extension, business practices. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Finnish city’s developing fashion industry. Here’s what I observed:

The Finnish Identity of Sisu

To understand environmental consciousness in Finland, one needs to first understand the psychology of its people. For many foreigners, Finns have a reputation for being stoic, serious, and taciturn. While Americans may find this personality type a little off-putting, that is in part due to our misunderstanding of sisu.

Sisu is a hallmark of Finnish character, described as everything from hardiness to bravery to tenacity. It’s a Nordic pragmatism that solidified into a national identity after years of struggling for independence from Sweden and Russia, a collapsed economy during World War II, and a close connection to natural resources (an estimated 73% of Finland remains forest). In between the political and the environmental emerged a Finnish identity that has come to value practicality and rationalism. And with little money and a limited amount of resources until quite recently, Finns have used that practicality and rationalism to become incredibly innovative in industries ranging from tech to hospitality to fashion.

Nomen Nescio founders, Niina and Timo Leskelä, who embody Sisu.

Nomen Nescio

The Landscape of Finnish Fashion Today

With less than 700,000 residents in Helsinki, the buying power of the city’s market is small. Coupled with the Nordic penchant for dressing in practical, all-weather clothes, it’s perhaps understandable that Finland isn’t quite the fashion capital as its Scandi cousins, Sweden and Denmark. But, small pockets of inspiration exist in Helsinki—you just have to know where to look.

If you know one fashion brand from Helsinki, it would undoubtedly be Marimekko. What Ralph Lauren is to the U.S., the poppy-filled vibrantly colored brand is to the average Finn. While Marimekko may not represent the everyday garments of Finland, there remains a national pride in the brand, making it one of the country’s most important cultural exports.

But for the average Helsinki native, perhaps a larger-than-life screenprinted flower or the brand’s popular striped jokapoika shirts aren’t office-appropriate. In that case, many Helsinki men enjoy FRENN, a local brand that stocks rich chocolate corduroys, merino wool polo-neck sweaters, and marled wool overshirts. For more utilitarian garments – remember, Helsinki is a coastal city off the Baltic sea – locals may grab an insulated coat from local brands Luhta and Makia. Of course, there is always the option to shop for international brands at Stockmann, Helsinki’s answer to Bloomingdales or Selfridges, stocking international brands that have a little more adventurous designs than most native Finnish brands.

Kaartinen & Kuusela

Kaartinen & Kuusela

Old is New Again

Given Helsinki’s cultural allergy to wastefulness, it should surprise no one to know that the capital’s second-hand market remains a strong component of the local fashion market, so much so that an outpost of a popular second-hand store, Relove, can be found at the Helsinki Airport. Look hard enough and you may spot some Ralph Lauren Purple Label or a heavily marked down Barbour Bedale that just needs a bit of wax to give it new life.

To stay competitive in the market, some vintage clothing stores are looking for ways to stand out. One in particular, Kaartinen & Kuusela, has become a go-to stop for menswear enthusiasts who are in the market for a suit. Offering two floors of options, one can find everything from Armani two-pieces to Brioni sport coats and Burberry tuxedos. While it is always a gamble, in terms of fit, when buying second-hand, Kaartinen & Kuusela has gone one step further in the retail process: onsight tailors will alter, hem, or take in your garments to reduce the risk of their products being put in a landfill if they don’t fit correctly.

If Kaartinen & Kuusela’s success is any indication of Helsinki’s fashion market, it shows that Finland is the perfect testing-ground for brands to try something new. With a low population and a small fashion export market, Finnish brands can easily pivot and experiment without destroying their bottom line. From large brands like Marimekko who has been experimenting with plant dyes to smaller indie brands like VAIN that uses recycled denim, at every level of the local fashion industry the conversation on how to future-proof their product offerings is taking place.

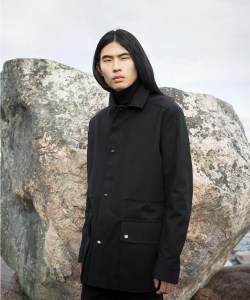

But, of course, minimizing waste and finding alternative dyes aren’t the only ways to be curbing a brand’s environmental footprint. Lessening consumption and minimizing production output help to mitigate a brand’s impact. To accomplish this, brands are moving more towards a capsule wardrobe, keeping one’s closet bare to easily mix-and-match key pieces. Unisex brand Nomen Nescio is at the forefront of this concept. With just a handful of all-black designs in quality fabrics that will last for years, both men and women can build a wardrobe that is specifically designed to combat overconsumption.

A look from Nomen Nescio.

Nomen Nescio

The Future of Design

Interestingly, some of the biggest names in Finnish fashion don’t even have labels of their own, or jobs for that matter: they’re the students at Aalto University. Named after Alvar Aalto, the famed Finnish architect, it only makes sense that the university remains one of the most innovative universities in Europe, most specifically in their Fashion, Clothing, and Textile Design program.

While the university hasn’t the same notoriety as Parsons or Central Saint Martins (we can blame this on the Finnish tendency towards humility), the impact of this program is felt throughout all levels of the global fashion industry. Graduates from the program have gone on to work for major houses such as Chanel, Louis Vuitton, and Hermés. In fact, many brands specifically seek out Aalto students, who have long been judges’ favorites for the prestigious Hyères Fashion Festival over the last decade.

Aalto’s mission has been to foster innovation and let fledgling designers grow through competitive opportunities, like Hyères, but also through on-site experimentation. Sarah Hudson, a communications manager at Aalto, mentions this freedom to create, giving as an example a student this year who used a 3-D printer and wood pulp to make an eco-friendly alternative to glitter. Students’ collections can be equally innovative, such as Sofia Ilmonen, who created an entirely modular collection made with small loops and buttons to turn, say, a shirt into a dress in minutes. In fact, it was this collection that secured Ilmonen a €20,000 from Mercedes-Benz during Hyères in 2021.

Aino Ojala, I Feel You 2023, MA Thesis

Aalto University

A Greener Way of Living

To build eco-consciousness into the DNA of a brand isn’t a simple feat. It’s easy to say the right words, but to execute is another thing entirely. While I have found myself, time and again, disappointed in the greenwashing that permeates the fashion industry, it has been refreshing to get acquainted with brands that aren’t leaning on a few marketing terms to do all the heavy lifting.

Instead, the Finnish inclination towards practicality has built a vibrant (albeit small) fashion community that consciously thinks about reducing waste, recycling materials, and reducing overconsumption. As for me on my farm? I may have to get a little more sisu in my own way of doing things to leave this acreage a little better off than how I found it.

Credit: robbreport.com