The creation of Lockheed Aircraft Corporation in 1926 was Allan Loughead’s second foray into airplane construction.

His first company, Loughead Aircraft Manufacturing, built a few products between 1916 and 1920. When he started his next aviation enterprise, he decided to use the phonetic spelling (Lockheed) of his Scottish-heritage surname (Loughead) to encourage proper pronunciation of the moniker. He would legally change his name to Allan Lockheed in 1934.

Lockheed Aircraft’s first successful project was the Vega, introduced in 1927. A high-wing, single-engine monoplane, the Vega’s selling point was speed, which would also be the performance highlight of Lockheed types to follow.

Early Successes and Challenges

The Vega found favor with some airlines (Braniff, Bowen, and Hanford’s Tri-State among them) but established its fame as a racing aircraft favored by renowned pilots of the day, most notably Amelia Earhart, who earned fame in her Vega as the first woman to fly the Atlantic, and Wiley Post, who set new records in his Vega named Winnie Mae.

In 1929, the Detroit Aircraft Corporation, a burgeoning aviation conglomerate, purchased a majority interest in Lockheed. Displeased with the takeover of his company, Allan Loughead resigned. After the stock market crash of October 1929, the Detroit Aircraft Corporation faced a tailspin of mounting losses, and Lockheed Aircraft descended into bankruptcy in 1932.

Before the manufacturer landed in receivership, the Lockheed Model 9 Orion was introduced in 1931. Designed specifically for use as an airliner, the Orion was a low-wing, single-engine aircraft featuring a new concept: retractable landing gear.

A New Beginning

Fortunately, the Lockheed Aircraft Company was not left to die. A group of investors bought the franchise for a mere $40,000. Among them, Walter Varney and Thomas Fortune Ryan III held a deep appreciation for Lockheed’s innovative designs. Varney employed both Vegas and Orions in his airline ventures. Ryan would eventually take over the aforementioned Vega operator, Hanford’s Tri-State – renamed Hanford Airlines – and build it into Mid-Continent Airlines.

In addition to Varney and Ryan, other investors included brothers Robert and Courtlandt Gross, who would remain with Lockheed until the 1960s. The company’s founder, Allan Loughead, pursued other interests, including real estate, and served as a consultant to his namesake aircraft company in later years.

The Lockheed Twins

Known for speed, Lockheed channeled resources into a twin-engine, all-metal airliner to outpace rivals like the Boeing 247 and Douglas DC-2.

L-10 ELECTRA

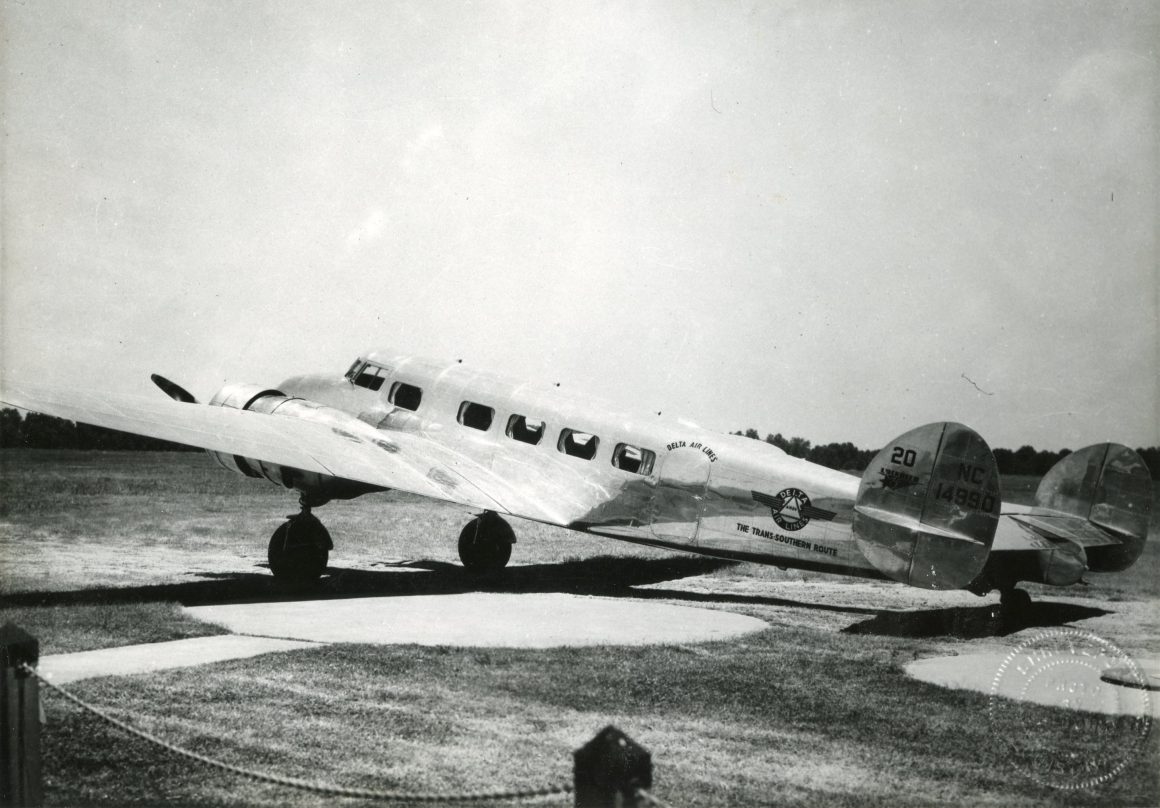

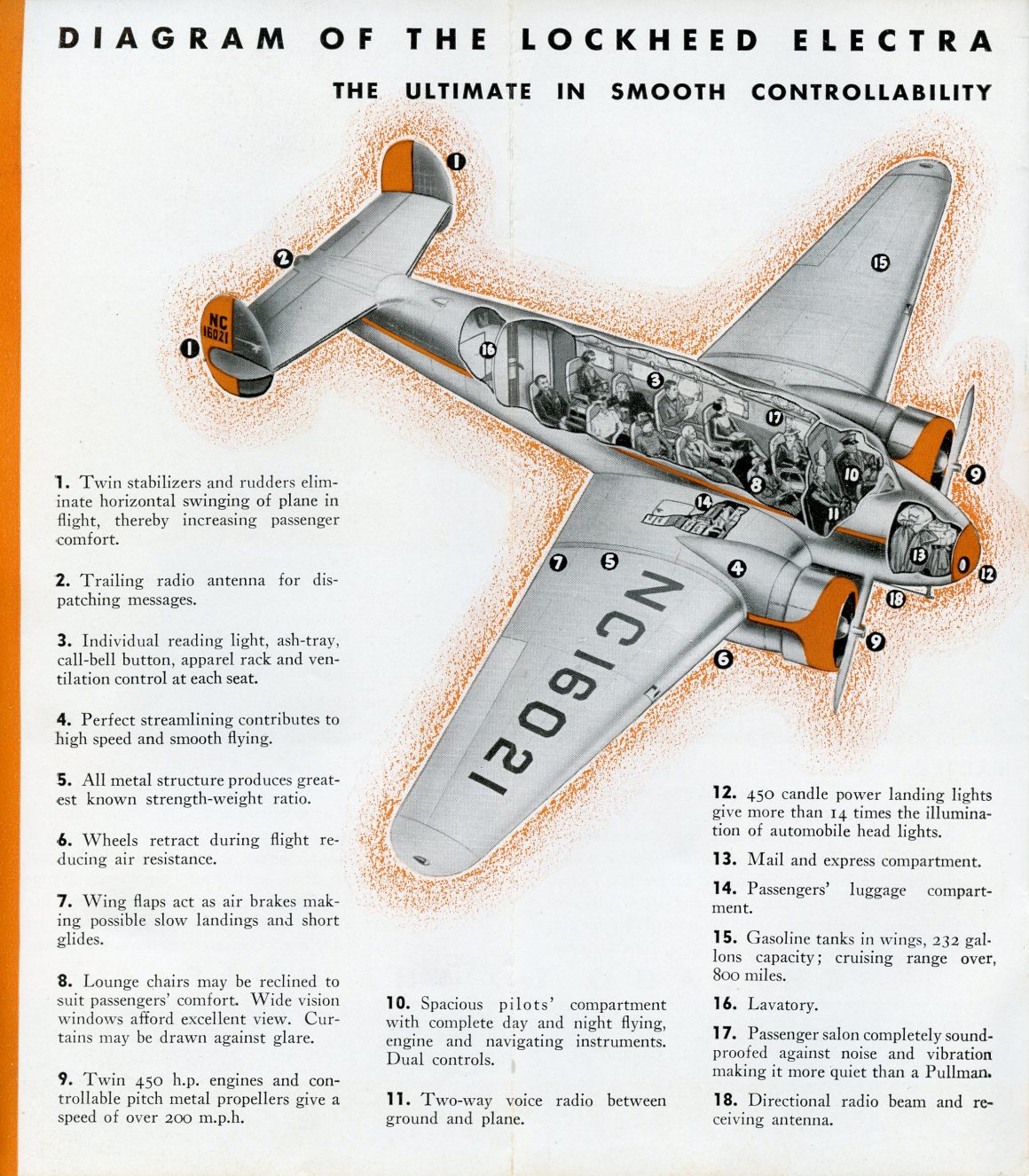

Developed and tested in 1932 and 1933, the 10-passenger Lockheed L-10 Electra debuted in 1934. The first units were delivered to Northwest Airlines that same year, followed by shipments to Pan American Airways for its subsidiaries, including Aerovias Centrales in Mexico, Pacific Alaska Airways, and Cubana. Other North American airlines that ordered the Electra included Braniff, Canadian Airways, Chicago & Southern, Delta, Eastern, Hanford (later Mid-Continent), and National. The type also found buyers among carriers in Europe, South America, and Australia.

A unique variant of the Electra, the Model 10-E, gained fame when Amelia Earhart flew it during her ill-fated attempt to circle the globe. Tragically, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, vanished near Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean on 2 July 1937.

Another Model 10-E served the U.S. Army as a testbed for cabin pressurization, a pioneering idea later implemented commercially by Boeing in its Model 307 Stratoliner, launched in 1939. In total, Lockheed produced 149 L-10 Electras, with 115 delivered as commercial airliners and the rest sold to private buyers and military customers.

ELECTRA JUNIOR AND L-14 SUPER ELECTRA

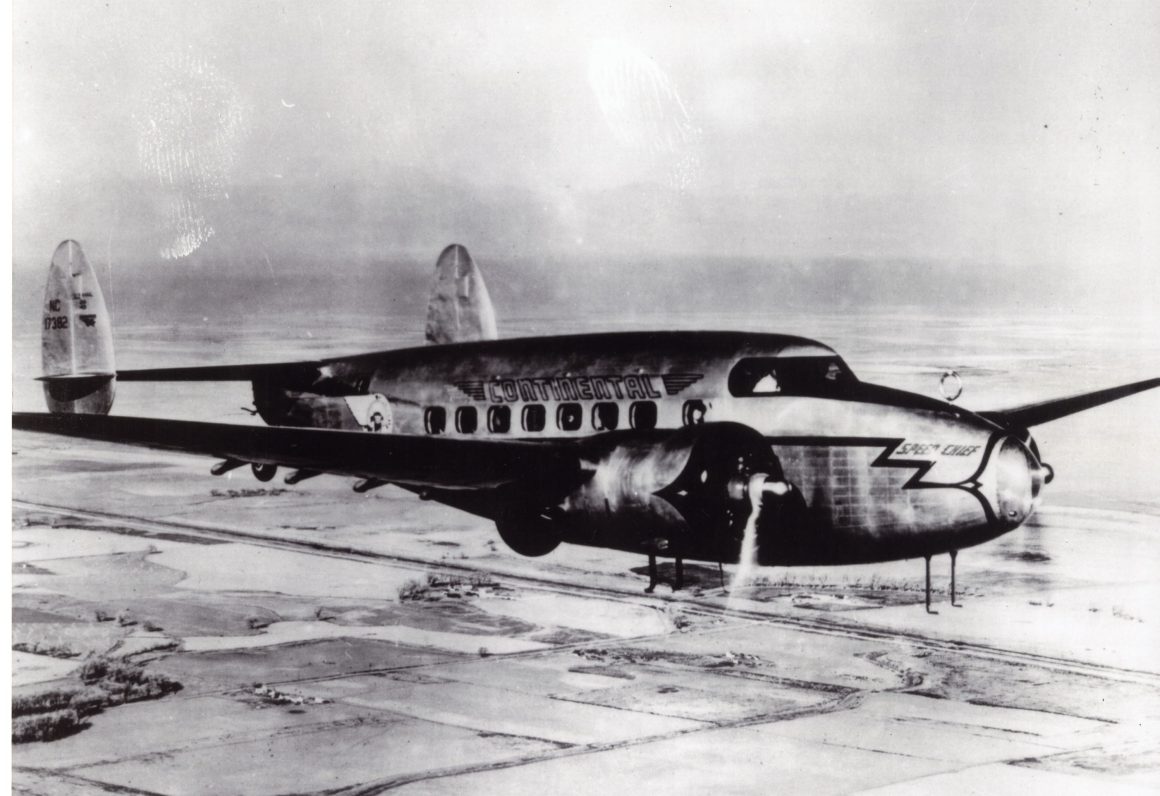

Building on the original Electra’s design, Lockheed built 130 Model 12s and 212s, referred to as the Electra Junior. Intended for use on low-traffic airline routes (the type accommodated only six passengers), the Electra Junior found its success as a corporate and personal aircraft. Only a few were sold to airlines. The original British Airways (1935-39) ordered two, National Parks Airways ordered two, and Walter Varney’s Varney Air Transport – soon to be renamed Continental Air Lines – took delivery of three.

Following the L-10, Lockheed introduced the L-14 Super Electra, a 14-passenger aircraft. It attracted orders from airlines worldwide, including Trans-Canada Air Lines, British Airways, LOT Polish Airlines, and Air Afrique. However, Northwest Airlines was the sole buyer in the United States, dubbing its L-14s “Sky Zephyrs.” Two of these later transferred to Continental Air Lines for a short stint.

A design flaw in the L-14’s twin vertical tail fins was corrected, but only after Northwest lost one of its Sky Zephyrs due to an in-flight failure of the fin assembly. Several other accidents led Northwest to abandon the type after the company introduced Douglas DC-3s in 1939.

L-18 LODESTAR AND L-75 SATURN

The ultimate model in the Lockheed Twin series was the 14-passenger L-18 Lodestar, introduced by Thomas Fortune Ryan III’s Mid-Continent Airlines in March 1940. Like the other Lockheed Twins, the Lodestar was popular with military and corporate customers but lost favor with most airlines after World War II as surplus C-47s (DC-3s) became plentiful and newer, modern twin-engine types were introduced.

Ted Baker’s National Airlines never operated DC-3s. Instead, the carrier kept Lodestars in service on some routes until 1959.

After the war, Lockheed also developed a high-wing, 14-passenger aircraft designed for local service operators. Dubbed the L-75 Saturn, the company halted production of the type, and the design was shelved for the same reason given for the Lodestar’s demise: a glut of less-expensive, war surplus C-47s and competing designs from other manufacturers.

The Lockheed Constellations

WARTIME SHIFT AND L-049 DEBUT

By the time the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Lockheed had made a dramatic comeback from its bankruptcy in 1932. In addition to civilian customers, the company found success in manufacturing aircraft for the military, all of which took place in Burbank, California, at Lockheed Air Terminal (the former Union Air Terminal).

Howard Hughes, the major investor in Transcontinental & Western Air (TWA)—later renamed Trans World Airlines—worked with Lockheed engineers to create specifications for a pressurized airliner that could carry 44 passengers nonstop between Los Angeles and New York. Hughes wanted the first delivery positions for this revolutionary aircraft reserved exclusively for TWA.

The new 4-engine aircraft was designated the Lockheed Model L-49 and given the stellar name Constellation.

During wartime, manufacturers halted all commercial airliner production and focused on designing and constructing aircraft for the armed forces. Engineers continued developing the L-49, now assigning it the military designation C-69 for use as a troop carrier.

After the war ended, Lockheed prepared the Constellation for its airline debut, and TWA launched scheduled L-049 Constellation service in February 1946. The “Connie” became the first post-war pressurized airliner to enter service and reigned as the premier airliner of its era.

UPGRADES AND SUPER CONSTELLATIONS

Lockheed continued to improve on the Constellation, introducing various upgraded models – featuring more powerful engines and larger, more luxurious cabins – every few years. The L-649 entered service with Eastern Air Lines in June 1947. Eastern Air Lines launched the L-649 into service in June 1947, promoting it as their “New-Type Constellation,” though the L-749 soon surpassed it. Engineers equipped both versions with an optional removable cargo pod, dubbed a Speedpak, which attached to the aircraft’s underside.

In 1953, Lockheed debuted the L-1049 Super Constellation, enabling TWA to schedule nonstop eastbound flights from Los Angeles to New York. Previously, early Constellation models required a scheduled stop en route, as nonstop flights depended on weather conditions and the aircraft’s load.

Subsequent improvements on the Super Constellation included the L-1049C Super C model, featuring new turbo-compound engines, and the most popular of the series, the L-1049G Super G Constellation.

TWA AND EASTERN AIR LINES WERE PROLIFIC CONNIE OPERATORS

TWA and Eastern Air Lines operated the largest Constellation fleets in the United States, and both airlines were closely associated with the tri-tailed airliners.

The Constellation series was also very popular with foreign carriers. By 1957, Super-Gs were crossing the North Atlantic wearing the colors of Air France, Iberia, KLM, Lufthansa, and Trans-Canada, in addition to TWA. Cubana’s Super Gs flew passengers from New York to Havana, and VARIG’s connected the U.S. with Brazil. While Northwest operated the type across the North Pacific, QANTAS Super Gs carried passengers from San Francisco and Honolulu to Sydney.

The final model in the Super Constellation series was the L-1049H Super H Constellation, which featured three different configuration options: all-passenger, all-cargo, or combination passenger/cargo.

In October 1958, the De Havilland Comet 4 and the Boeing 707 ushered in the jet age for countries outside of the Soviet bloc (the USSR had introduced the Tupolev TU-104 as its first jet airliner in 1956). This would swiftly end the big piston-powered airliners that plied long-distance routes.

THE STARLINER

Douglas Aircraft introduced its ultimate reciprocating-engine propliner, the DC-7C Seven Seas, in 1956. Lockheed also created a top-of-the-line piston-engined, propeller-driven aircraft to serve as the last of the great breed. It looked like a Constellation. But, the L-1649A Starliner, equipped with turbo-compound radial engines, was marketed as an entirely new type. With a range allowing TWA to fly the Polar Route from Los Angeles and San Francisco nonstop to London or Paris, the airline decided to market its L-1649As as Jetstreams rather than Starliners.

Only 44 L-1649As were built, with Air France and Lufthansa operating Starliners in addition to TWA.

The Turboprop L-188 Electra

While Douglas, Boeing, Martin, and Convair had each contributed products to America’s postwar airliner market, none of them had decided to follow through on a commercial transport design with turboprop engines – the hybrid combination of turbine power and propellers, commonly referred to as a jet-prop or prop-jet.

In 1954, American Airlines and Eastern Airlines expressed interest in a turboprop airliner that would be bigger and faster than the British Viscount. Lockheed was in the process of building its first military turboprop, the Allison-powered C-130 Hercules, so the company was gaining the experience needed to design a commercial jet-prop transport. The C-130 itself would become the basis of a commercial cargo aircraft, the L-100 Hercules, employed by Delta Air Lines, Alaska Airlines, and other carriers in the 1960s.

The aircraft that developed from the initial meetings between Lockheed, American Airlines, and Eastern was the L-188.

In one of the oddest marketing decisions ever made, Robert Gross gave the L-188 the name Electra, the same name that had graced 1934’s Lockheed model L-10. When speaking of flying aboard an Electra, how was one to know if you meant the little twin-engine airliner from the 1930s or the modern 4-engine turboprop? But Electra it would be.

The Lockheed L-188 Entered Service in 1959

The first Lockheed L-188 entered service with Eastern Air Lines on 12 January 1959. American was next, starting Electra operations on January 23, two days before the airline launched its first pure-jet service with the Boeing 707.

With its four large Allison turboprop engines, a cruising speed of over 400 mph, and a passenger capacity of 65 or more, the L-188 appeared to be ready to fulfill its requirements as a short-to-medium haul airliner capable of operating from airport runways too short for the new jetliners.

A Design Flaw Leads to Tragedies

Less than two weeks after American’s Electra inaugural, one of the company’s L-188s, christened Flagship New York, crashed into the East River on approach to New York’s LaGuardia Airport. Investigators attributed the accident to the crew’s inexperience with the type and weather conditions at the airport.

On 29 September 1959, a Braniff Electra fell from the night sky en route from Houston to Dallas. Before the investigation for that accident was complete, a Northwest Orient Airlines Lockheed L-188 met a similar fate, falling to the ground at Tell City, Indiana, on 17 March 1960.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) placed speed restrictions on all Electras shortly after the Northwest crash. Lockheed’s new turboprop was earning an unwanted reputation, and the public began avoiding it.

WHIRL MODE

After a thorough investigation, authorities attributed the crashes to a phenomenon known as whirl mode. This condition results in severe vibration that could cause a wing to separate from the aircraft in flight due to “flutter induced by oscillations of the outboard nacelles.” The Electra’s large engines, mounted on stubby wings, needed more secure bracing, while the wings themselves needed strengthening.

The manufacturer launched a modification effort called the Lockheed Electra Action Program—LEAP—to address a recognized design flaw (though some sources mistakenly claim the acronym stands for Lockheed Electra Achievement Program). After completing the LEAP modifications and returning the aircraft to their airline owners, authorities removed the speed restrictions.

When the modified Electra reentered service, most airlines chose to rebrand them as Electra II, Super Electra, or Electra MK II. The type recovered from its early bad publicity and went on to provide many years of reliable service for airlines worldwide.

Lockheed’s Commercial Era Comes to an End

Unlike Boeing, Douglas, and Convair, Lockheed did not produce a first-generation commercial jetliner. However, the company maintained a robust production of aircraft, missiles, and other military assets.

The manufacturer would not participate in the airliner marketplace again until the company created its widebody L-1011 TriStar, which would be the final type of commercial aircraft built by Lockheed.

Between 1968 and 1984, Lockheed manufactured 250 TriStars. The type’s commercial operations ended in 2008, and just one final L-1011 remains in the air today.

Total

0

Shares

Credit: avgeekery.com