The story of UAL Flight 232 rewrote aviation history.

On 19 July 1989, McDonnell Douglas DC-10-10 serial number 46618/118 registered as N1819U and flying as United Airlines (UA) flight 232, departed Denver’s Stapleton airport at 1409 local time bound for Chicago O’Hare airport and continuing on to Philadelphia.

One hour and seven minutes into the flight at flight level 370 (37,000 feet), while in a shallow right turn, the flight crew heard a loud bang followed by vibration and shuddering. The number 2 engine, mounted in the vertical stabilizer on the DC-10, had suffered an uncontained failure. The shrapnel generated by the failure severed nearly all of the hydraulic lines routed through the area, causing severe controllability problems for the flight crew. This recording of the radio exchanges between the crew and the ground after 7700 was uploaded to YouTube by adliasea.

The hydraulic pressure in all three independent systems in the aircraft was reading 0. The jet began a descending right turn, which the crew could only partially control using throttle settings for the two wing-mounted engines. At 1520, the crew declared an emergency and was given vectors to Sioux City Gateway Airport (SUX) in Iowa by the Minneapolis Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC).

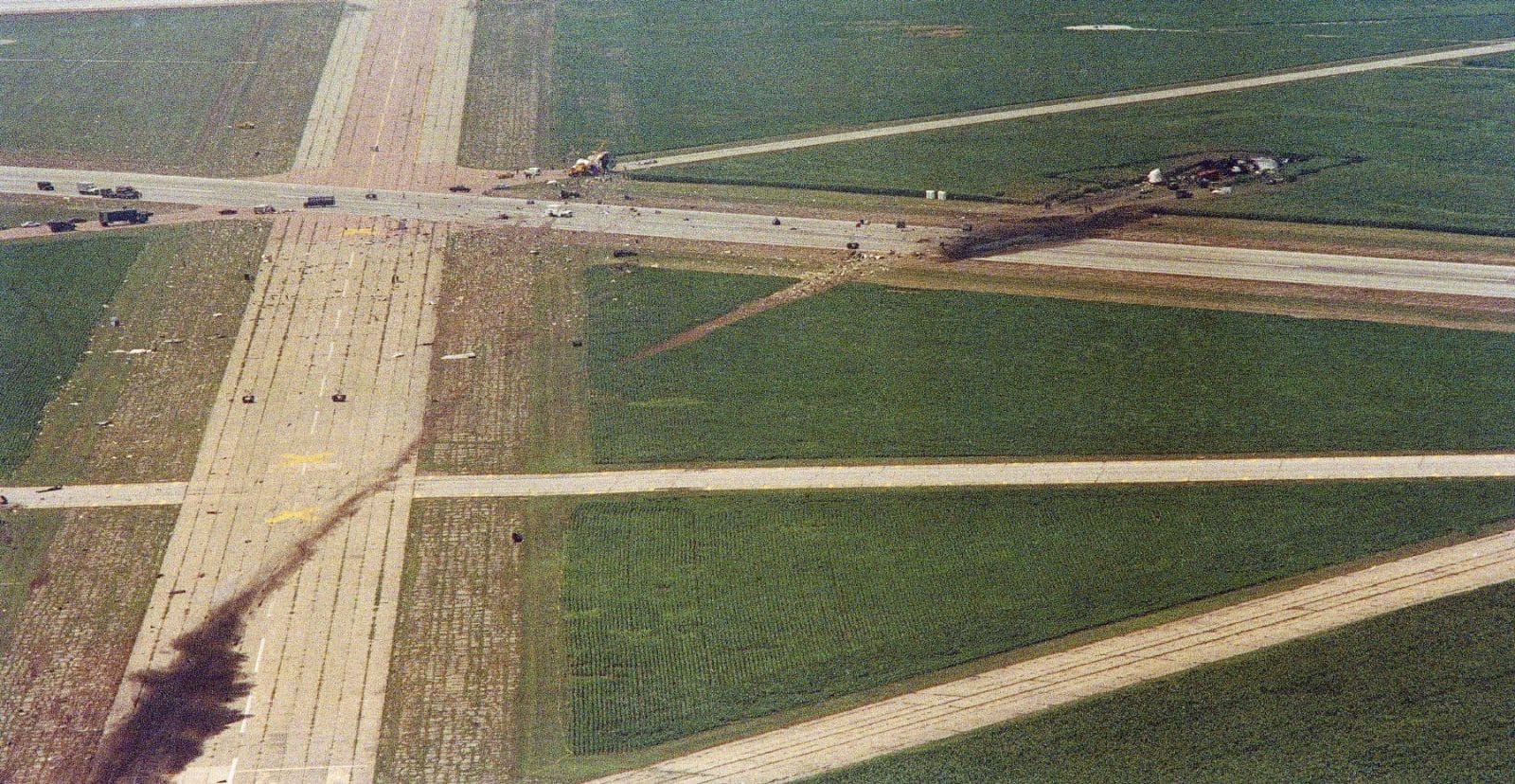

UAL Flight 232’s Crash Landing in Sioux City

The aircraft circled to the right several times while descending. The jet made an approach at 215 miles per hour but with a high sink rate. At the last moment, the aircraft began to porpoise again and pitched down, impacting short of runway 22 and right of the centerline. The right wing impacted first. Then the jetliner rolled inverted, caught fire, and broke up in a cornfield.

Captain Alfred C. Haynes, First Officer William R. Records, Second Officer Dudley J. Dvorak, and Training Check Airman Captain Dennis E. Fitch (who was deadheading on the flight before coming to the flight deck to assist) had done their best given a really dire set of circumstances.

The accident investigation revealed that when the engine failure occurred, a fan disk disintegrated. The DC-10 had been delivered in 1973 and had amassed 43,403 flight hours over 16,997 cycles at the time of the accident. The lack of hydraulic pressure, caused by the severing of the hydraulic lines near engine 2, took the aircraft’s controllability on approach away from the crew.

The engine failed because of a previously undetected fatigue crack near the shaft in the engine’s stage 1 fan disk. Three months after the crash, the crack and several individual blades were finally located in a cornfield.

An impurity in the disks’ titanium caused the fatigue crack. Concerned about a recurrence, many of the stage 1 fan disks on in-service General Electric CF6 engines were inspected. At least two other stage 1 fan disks were found to have similar defects. Hydraulic fuses were installed in the number 3 hydraulic system in the area below the number 2 engine on all DC-10 aircraft to ensure controllability in the event that all three hydraulic lines should be damaged in the tail area after the UAL Flight 232 accident.

Investigation, Aftermath, and Legacy

111 of the 296 souls on board perished in the accident. Several factors contributed to the survival rate, including good weather, daylight, the timing of shift changes at local hospitals, and the presence of Iowa Air National Guard personnel at the airport that day.

Although the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) concluded that a successful landing was virtually impossible, the flight crew, who all survived, recovered, and continued their airline careers, deserve a great deal of credit for how much worse this accident could, maybe even should, have been.

In the years before this event, no one had ever survived the complete loss of flight controls in an airliner—until 19 July 1989. When Captain Haynes flew his final airline flight before retirement, he was joined on the flight by several of the first responders and survivors of UAL Flight 232.